June 28, 1947

ADOPTED BY: BILL AND DEBBIE PALMER

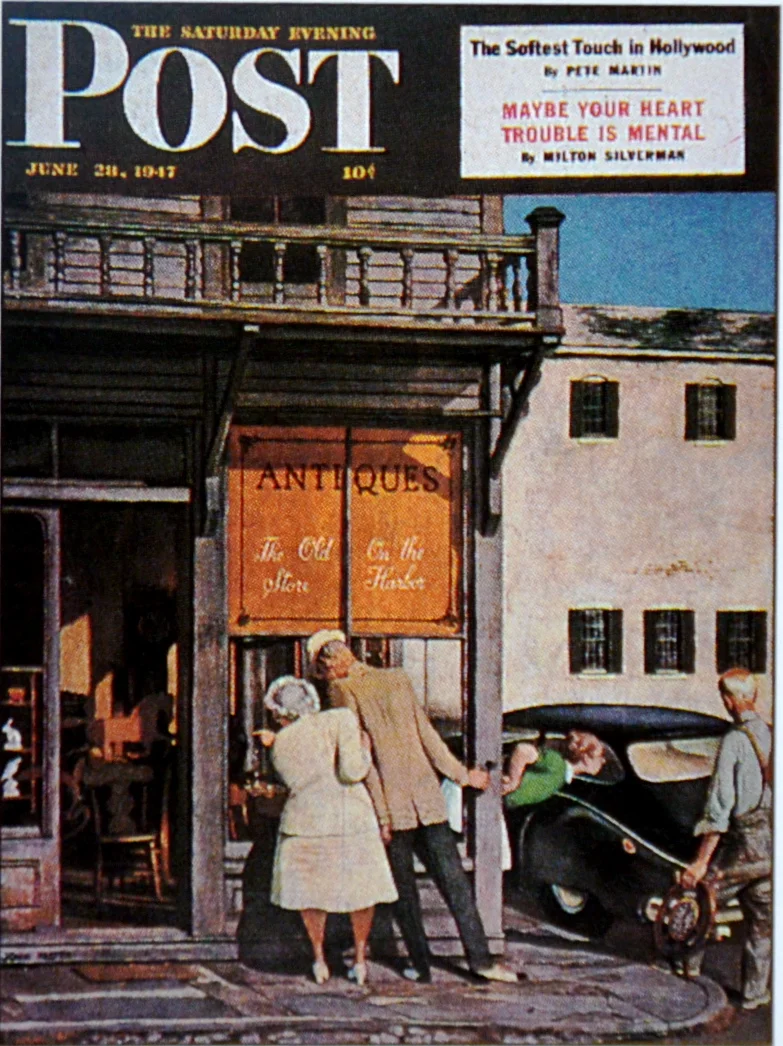

Residents of Connecticut will recognize the setting of John Falter's cover. The store is patterned after one the artist has patronized in Southport, Connecticut. It occurred to Falter that rarity is a relative thing, and that dealers in the old and unusual might be interested this summer in the new and unusual--a new car. If you could hear the antique dealers in his painting, you would hear them making the same sighs of awe and delight over the gleaming new automobile in which their customers arrived as the antique hunters are making over the pre-automobile chair. "How I'd like to have that," is what all concerned are saying about different subjects.

August 2, 1947

ADOPTED BY: MIKE & ELAINE COLLET

When he decided to paint a characteristic New England summer-resort scene, John Falter chose Ogunquit, Maine, where he has spent his vacations for the last ten years.

The hotel is one the artist always thought typical, and he has drawn it very true to life. The ocean is behind; you can see a glimpse of that cold Maine water to the left of the inn. There is a summer theater in Ogunquit so, in painting the parade of vacationists on their way to the beach, Falter included a couple of figures he thought might represent the summer-theater staff. The skinny lad in shorts is Falter's unflattering idea of a playwright. The fat gent with the beard is Falter's friend and stand-by character, the radio actor, Jack Smart

September 27, 1947

ADOPTED BY: MADALINE & LEON WILHELM

John Falter's scene for the harvest time painting is his native Midwest; he sketched those barns and the rail fence near Weston, Missouri. The farm, long owned by the Blythe family, is one of the oldest in Northwestern Missouri. Falter completed the painting when he got back to his home in Pennsylvania, and the trees, the apple pickers and the farm woman are done from memory. It wasn't hard to recall similar scenes from his own boyhood, although as he worked, the phase of apple picking Falter recalled most vividly was fresh apple pie. In a burst of nostalgia he asked to have it for dinner. He enjoyed every bite, and it wasn't until later that it occurred to him the pie he had eaten with such pleasure was cherry.

November 1, 1947

ADOPTED BY: LARRY & CHARLOTTE NEDROW

IN TRIBUTE TO BUTCH & DOBEY HAWS

It seems to John Falter that one of the best moments in football is that certain going-up moment when the squads trot out on the field. For one thing, the team in which your hopes are invested always looks pretty good at that stage; even an outfit that is going to take a terrific lacing when the whistle blows can look like champions executing this maneuver. The politic artist said the squad might be that of any school whose colors are orange and black. That takes in a fine range of educational institutions and makes it almost impossible that Falter should have picked a loser. He chose the Princeton stadium for background, and Falter Hypothetical Institute, taking the field, seems to be based on Princeton, with the Tigers' stripes.

November 15, 1947

ADOPTED BY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

J.P. Morgan did not feel better after his greatest multi-million-dollar merger than a boy trapper with his first real catch. Like the kids crossing the winter wheat in John Falter's painting, Falter used to trap skunks, getting about $1.50 a pelt. He was well satisfied with this price until someone told him fur prices always rose in the spring. Then young Falter grew cagey and planned to make a killing; he would store his catch in the woodshed and sell nothing until spring. Might have worked, too, except for one thing. By spring, all the hair had fallen out. ("Undaunted," adds his assistant, Dick Lyons, "the boy trapper fashioned a few crude brushes and with them he has been painting crudely ever since.")

January 16, 1943

ADOPTED BY: BUTCH & DOBEY HAWS

IN TRIBUTE TO THE RICHARDSON FOUNDATION

No one who lives in a big-city apartment house has to be content with his own observance of New Year's. He takes part willingly or not in parties above, below, and across the way. What interested John Falter was the possibility of showing the New Year’s arrival as it touched seven or eight homes, all in compact layers. He seems to have covered all ages, from the baby to old age, in the person of the old gentleman alone except for his hunting trophies. The scene is more or less based on Gramercy Park, New York, where Falter occupies a second-story apartment. It's our opinion that at the hour in question the old gent's moose head probably is making more sense than most of the more animate characters.

February 7, 1948

ADOPTED BY: DAN & BETH HERRING-HILL

The scene of John Falter's painting is Central Park, New York.

Falter is a country boy, and it has always seemed strange to him that there should be skating just across the way from big-city buildings. He has also been puzzled by the variety of skating costumes he sees on the ice in Central Park--ranging from the most colorful of outdoor clothing to the most sedate business outfit. The gent in the dark overcoat, for example, must have put his skates on during a meeting of the board of directors. "But the real reason I painted the cover," Falter said, "was to see if I could paint that many windows. I figure that if everyone who lives behind all those windows would buy a copy of the Post, the issue would be a sellout."

February 28, 1948

ADOPTED BY: RON & JANE BODEN MCGINNIS

The locale of John Falter's painting is New York; he has assembled a number of big-city winter sights and characters before a flower shop which is a composite of several on Madison Avenue. Falter painted his cover in December. It was cold in New York--where wasn't it? -- and the cagey artist did most of his investigating behind glass, riding up and down on a Madison Avenue bus. He figured the frozen-faced snow shovelers must get an ironic laugh from the fact that inside the flower shop window it is fall, midsummer or spring, at the customer's choice. Falter delivered his picture just before the first of the winter's oversize snowstorms hit New York. Then the artist hauled out for Arizona, where you may enjoy scenes like this in comfort.

March 27, 1948

ADOPTED BY: THE RIVERSIDE CATTLE COMPANY

It was John Falter's big idea to show that life in a home in the country is very much like life in a home in the city these days. Time was when the farm family had to do without some of the conveniences of city life--not to speak of the inconveniences--and Falter remembered that time. But when the artist began work on this painting he ran into trouble. Any scene he painted would have to be labeled "Farm Home, 1948," because a farm home in 1948 can't be told from a city home. You will see that he got around this by putting the farmer in overalls and hanging a picture of a prize-winning bull on the wall. The bull is fictitious. This is a real farm family, however--Mr. and Mrs. Ray Clark and their children, who live near Atchison, Kansas.

May 8, 1948

ADOPTED BY: CINDY GLENN GESS

Bill, the Birdhouse Builder, lives and builds in Artist John Falter's home town, Atchison, Kansas, and his birdhouses must be famous from the rice fields of Louisiana, where the ricebirds congregate, to the snow fields, where the ptarmigans hang out. For he gives the birds a joint painted so bright they could see it through a London fog. Bill, who is more formally Mr. William Kloeper, is eighty, and has built enough birdhouses for about 1400 pairs of birds.

When the West was still frontier, Bill drove the stagecoach from Casper to Thermopolis, Wyoming, and served in two important public capacities in Thermopolis--as town marshal and bartender. But he told Falter that the Old West was safer and quieter than many a modern city.

January 16, 1943

ADOPTED BY: ESTHER & RICHARD HALBERT

IN TRIBUTE TO GOV. DAVE HEINEMAN

This is John Falter's preview of next week's Republican convention, with a demonstration going on for someone. But you'll notice Falter made it impossible to read the names on the placards, nor is the candidate's face recognizable as that of any of the leading Republican hopefuls. But the enthusiasm shows one thing--he is clearly the man of the hour, the people's choice, the plumed knight. So it's easy to guess which man Falter had in mind--your man, of course. The white-coated gentleman in the lower right-hand corner will be easier to recognize, especially where the Republicans are making big medicine. He is Clarence Budington Kelland, whose stories are so familiar to readers of this magazine and who has long been a party leader.

July 3, 1948

ADOPTED BY: RIVERSIDE CATTLE COMPANY

IN TRIBUTE TO DOROTHY TOWLE

The men John Falter used as models for his golf painting will be surprised at what has happened to the course. The golfers were playing a course near Phoenix, Arizona. Falter added trees he thought would look more general.

The result is a Western course with Eastern trees, and it's a wonder anybody can win there. Falter thinks all the men he painted are giants of industry, and we would identify them but for the fact that Falter probably moved faces and figures around. The trouble with a picture like this is that it leaves everybody wondering if the sand-trapped gent got out. If an artist can take liberties with the scenery, then we can give you the ending. He laid that shot right into the cup, making the rest of them look like amateurs.

July 24, 1948

ADOPTED BY: RIVERSIDE CATTLE COMPANY

IN MEMORY OF THEIR GRANDPARENTS

Driving through Western Texas, Artist John Falter came across an unusual service for tourists. In case a

traveler wished to take home photographs showing him outdoing the cow punchers at their own game, an itinerant photographer had set up shop at a filling station on the Texas plains. While the tourists' car was being gassed up, he gave them a chance to be photographed riding one of the wildest steers Texas ever produced or staying aboard a bucking bronco in spite of the bronco's most violent efforts to toss them off. The photographer provided the steer and the bronco, and tough-looking animals they were, until you observed that they never moved. Anybody could look good riding this livestock-- the steer and the bronco were stuffed.

August 14, 1948

ADOPTED BY: KEVIN & JANET MALONE

Artist John Falter's setting for his surf-bathing cover is Ogunquit, Maine. He made his first sketches while spending the summer in Maine, beating the heat, but didn't get around to painting until last winter. By that time the lucky lad was in Phoenix, Arizona, beating the cold. The hotter that Arizona sun got, the more fondly the artist thought of Maine's cool air and cool spray. So he hired a couple of pretty models for the girls in the lower right, and went to work on a picture of Maine as remembered in the Southwest. The pretty girl in the left foreground, just emerging and shaking out her hair, often appears in Falter's cover paintings, but doesn't get a model's pay for her work. She is Margaret Falter, John's wife.

September 18, 1948

ADOPTED BY: RIVERSIDE CATTLE COMPANY

IN MEMORY OF GLENN & MARGARET WITT

Cover ideas are where you find them, and John Falter found this one last year while he was passing through the town of Pecos, which is deep in the Texas cow country. The movie house was getting a brisk play from the local cowboys and girls, and what should be luring them in but a cowboy picture. Falter quickly recognized that he had something, but it was January of this year before he could come back and go to work on it. In the finished painting, the Cactus Theater and the hatter's shop are real, the titles of the movies displayed on the marquee and on the bill boards are fictitious. So are the customers: Falter hit Pecos during such a bad stretch of weather last January that movie-goers just weren't venturing out.

November 20, 1948

ADOPTED BY: “SPORTIN’ FALLS CITY”

John Falter was in Atchison, Kansas, when he decided to base a cover on the fact that wives often generously consent to help their husbands pick out clothes. Falter had a store to use as a model--his father's. But to even things up, he did not use his father as the model for the clothing salesman. Readers are seeing here what the customers in Atchison never see. Selling clothes in the senior Falter's establishment is his old competitor, Jim Walsh, who runs a rival store. The customer is Cy Wetherford, of the city water department. The "wife" is Mrs. Rose Stuart, who works in a department store. Incidentally, the snappy grass-colored suit with the ripe stripe is one Falter junior dreamed up. His father wouldn't have it in the shop.

December 18, 1948

ADOPTED BY: ALYCE SCOTT

IN MEMORY OF PAUL SCOTT

John Falter's sledding hill is an imaginary one he designed as a boy, long before he had any idea of becoming an artist.

Where he grew up in Nebraska, the countryside was fairly flat. When Falter was the age of some of the boys in his picture, he used to imagine a hill like this one—steep enough, long enough (although you can't see that part) and with a sporting curve near the start of the runway. That, it seemed to him, would be the perfect hill, the very St. Andrews of sledding. He got around to painting the scene last fall while visiting Atchison, Kansas, when the temperature was ninety. The blue-and-tan sled belongs to a boyhood friend--and the friend's son. Falter recalled it from his own childhood; it was still in good shape.

February 5, 1949

ADOPTED BY: LINDA TUBACH BALSAMO

The original idea here was to show a new boyfriend undergoing a merciless inspection by the girl's family. John Falter wound up doing an even more harrowing variation of the theme. The girl, the mother and the clerical brother are only too attentive to the swain, but most of the household resoundingly ignores him. Falter used as a setting the home of Sid Castles in Geneva, Illinois. However, as artists will, he added wrinkles of his own, such as the picture in the center--an old chromo called The Tie That Binds. Falter says he saw this picture everywhere as a boy in Nebraska. As an adult, though, he has never been able to find anyone who ever heard of it.

February 26, 1949

ADOPTED BY: ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

Children living near Artist John Falter's country home are used to getting phone calls asking them to come in and pose. They had no trouble posing for this one: he simply wanted to see how they look starting out on a snowy morning to catch the school bus. There was plenty of snow out their way, too--Falter lives in a 144-year-old farmhouse thirty-five miles north of Philadelphia. The kitchen in the painting is his own, as it looked before the Falters modernized it. We think Falter is overly optimistic on one point. The mother of a family this big would be worn to a frazzle at this stage of the daily crisis called Getting Them Off to School. In reality, these are children of three families—the Kummers, the Chews and the Coltmans.

March 26, 1949

ADOPTED FOR: RICHARD M. & VIVIAN HALL

In this spring-house-cleaning scene by John Falter, one thing led to another. Take the man on the sidewalk. At first he was just passing by. Then Mr. Falter had him start poking through the trash. Then Falter had the lady of the house stop her rug cleaning to watch. If the nosy neighbor does find some unsuspected treasure in the rubbish, the lady will be down there to reclaim it faster than he can reach down to pick it up. You don't have to worry about the man wrestling that storm window down the ladder, either. Falter says he used to go through this routine with his father every spring. Invariably a sudden wind would come up at precisely the wrong moment, bending his father back at a perilous angle, but it never did topple him off.

April 30, 1949

ADOPTED BY: ALYCE SCOTT

IN MEMORY OF CAROL SCOTT

When John Falter's cover painting was accepted, there was lightning trickling down the sky beside the rainbow. Presently the Art Department began to worry--do lightning and rainbows ever show up at the same time? The ever helpful Weather Bureau was asked to look at the Post's storm--which has just doused midtown New York and is rumbling away beyond Central Park's man-made ramparts. "Fair and cooler," was the comment. "But we never saw a streak of lightning in such bright daylight. Of course, where weather is concerned, anything can happen." So the picture was delightninged, leaving only that sign of clearing weather, a patch of blue sky large enough to make a sailor a pair of breeches.

June 4, 1949

ADOPTED BY: BUTCH & DOBEY HAWS

IN TRIBUTE TO MERLE & TRULA BACHMAN

When John Falter was visiting his father in Atchison, Kansas, he phoned a neighbor who has a youngster in Atchison High School and said, "If we could persuade some of the boys and girls to go out by the river and look like a picnic, maybe they would all wind up on the cover of the Post." As the riverside rendezvous took place shortly after everybody had had the midday meal, Falter was astonished when the young folks turned up with several baskets, broke out a mountain of food and promptly ate it all up. Must be he doesn't know kids.

Falter made it an evening scene; that's the Missouri River shimmering in the moonlight, and the pleasant Missouri countryside beyond. It is not a very realistic painting, though. No ants in sight.

August 13, 1949

ADOPTED BY: BOB & MARY ELLEN GLENN

On the long fishing pier at Santa Monica, California, tourists from all over the United States stand packed together like sardines while they try to catch fish.

They are so grimly intent on their work or play or whatever it is that when a baited minnow smacks the water in all that silence, it makes quite a startling splash.

Many of the fishermen go through their routine calmly and expertly; occasionally a greenhorn flies into a tizzy, yelps for the landing net and hauls in a dwarf flounder or something else depressing. The kids have a swell time fussing with starfish or reading a wet comic page which was wrapped around a wad of bait. Artist John Falter was noncommittal about whether he caught anything-- besides a Post cover.

December 3, 1949

ADOPTED BY: MATT MOREHOUSE

John Falter chose a Christmas shopping scene which New Yorkers could enjoy to the full, but are apt to miss while endeavoring not to fall downstairs. As you look at the Gothic architecture of St. Patrick's Cathedral framed to the contrasting modern character of Rockefeller Center's principal Fifth Avenue building, you are standing inimagination of the edge ofthe mezzanine floor. But you'd better watch your step or you'll go down faster than the moving stairs do. The Christmas trees are by courtesy of Falter, who had to sweat while erecting them on his canvas, because he did the painting in steaming weather last summer. And did that whee him up to do his Christmas shopping early? The last we heard, he hadn't bought a thing.

January 7, 1950

ADOPTED BY: ESTHER & RICHARD HALBERT

Packing the portraits of some two hundred people onto one small canvas is quite a chore. As life wasn't long enough for individual sittings, John Falter's painting of the joint session of Congress in the House on January 5, 1949, was done from photographs. Mr. Barkley, who hadn't yet been sworn in as Vice-President, didn't make the cover, being off-scene at the right. The Senate's President Pro Tempore, Senator McKellar, was seated under the stars of Old Glory. Falter took one liberty; muttering "Excuse me," he moved Mrs. Truman from the Executive Gallery into the visible Diplomatic Gallery. Everybody will recognize on person in the picture, a relative of Mrs. Truman; how many more can you name before studying the chart on Page 73?

February 11, 1950

ADOPTED BY: DAVID CLARK FRAMING

When John Falter runs up to New York from the open spaces of Pennsylvania's Bucks County, he usually runs right downtown to The Players Club, from where, as his painting shows, he can regard the open spaces of Gramercy Park. In the park you see the statue of Edwin Booth, the club's founder, contemplating the citified version of a winter sports scene. Poet Percy Mackaye, a familiar figure around The Players, remembers that his great-grandfather loved to sit under the ancient tree at the left. Falter once had a studio in a building next to The Players; he says he has made his view of the park from a point about where the two buildings join, and between the third and fourth floors. Quite a stunt without a helicopter.

March 18, 1950

ADOPTED BY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

This cover landed John Falter in his second childhood. A man can't paint kites unless he flies a few, can he? Falter bought some Navy target-gunnery jobs--double-string rudder-control affairs like the red and blue ones in the picture--and Mrs. Falter became a kite widow. Then Falter and friend Arthur Naul built an eight-foot box contraption. The leviathan flew too until eventually it crashed, and now it will never fly again. As time went on, people got to inquiring whether those old guys always out there playing with the kites were balmy or what.

Finally, when the Post phoned Falter and asked him where under the sun his kite painting was, he sadly wrenched himself back into this vale of labor, and started painting, fast.

May 13, 1950

ADOPTED BY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

John Falter contends that nothing in the world smells as good as Missouri River Valley loam just after it has been plowed and rained on and is all excited about growing a new crop. Born and bred in that country, the man is biased. Is there a square mile in the U.S.A. where the vernal earth doesn't come mighty sweet? "How lovely the warm mud felt on my feet!" Falter says rapturously. "And what a beautiful sound it made--slup, slup, slup!" One editor worried, "Is Falter's barefoot boy true to life? My kids don't remove their sneakers before slupping. I hate to think bitterly of them, but they might even put on their Sunday shoes first." Falter's lad is normal: he'll be thought of bitterly when those black feet come home.

June 24, 1950

ADOPTED BY: DICK & JANE ANN HALL

Congratulations to this happy bride and groom, and to all the Junetide grooms and brides they symbolize. Felicitations to the weatherman--at least to his deputy, John Falter--for not pelting the joyful hour with lightning, cloudbursts and hailstones. Condolences to bad wishes to the guy with his arms innocently folded; he acts like one of those dopes who attend weddings for the sole purpose of tying rubbish on honeymoon cars. As for the uninvited guest, whose wife has just sent him to the grocery store to buy stuff for supper--why, congratulations to you, sir! (It's probably his nineteenth wedding anniversary and he has just remembered it.) Condolences to the bride's mother--or is it the groom's mother?--as she drops the traditional tear. And all bad wishes.

September 2, 1950

ADOPTED BY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

Old Baldy, the pitcher with the exquisite form in John Falter's scene of stirring diamond strife, is gravely contemplating picking the runner off second base. If he doesn't mind that the runner is breaking the softball law by being off base, we're certainly not going to worry about it. Maybe the umpire was selected because he has a natural chest protector, and he makes up the rules as he goes along. That gal at the plate obviously has power. If Baldy ever gets his arms untangled, she'll nick him for a liner over third and through a window of the blue automobile. Then everybody will jaw bitterly about whether it's a homer, a foul or a ground-rule double, until the ump rules, "I put both teams out of the game! Let's go eat!"

All covers are copyright of the Saturday Evening Post Society.