July 1, 1961

ADOPTED BY: BART & GAYLE KELLER

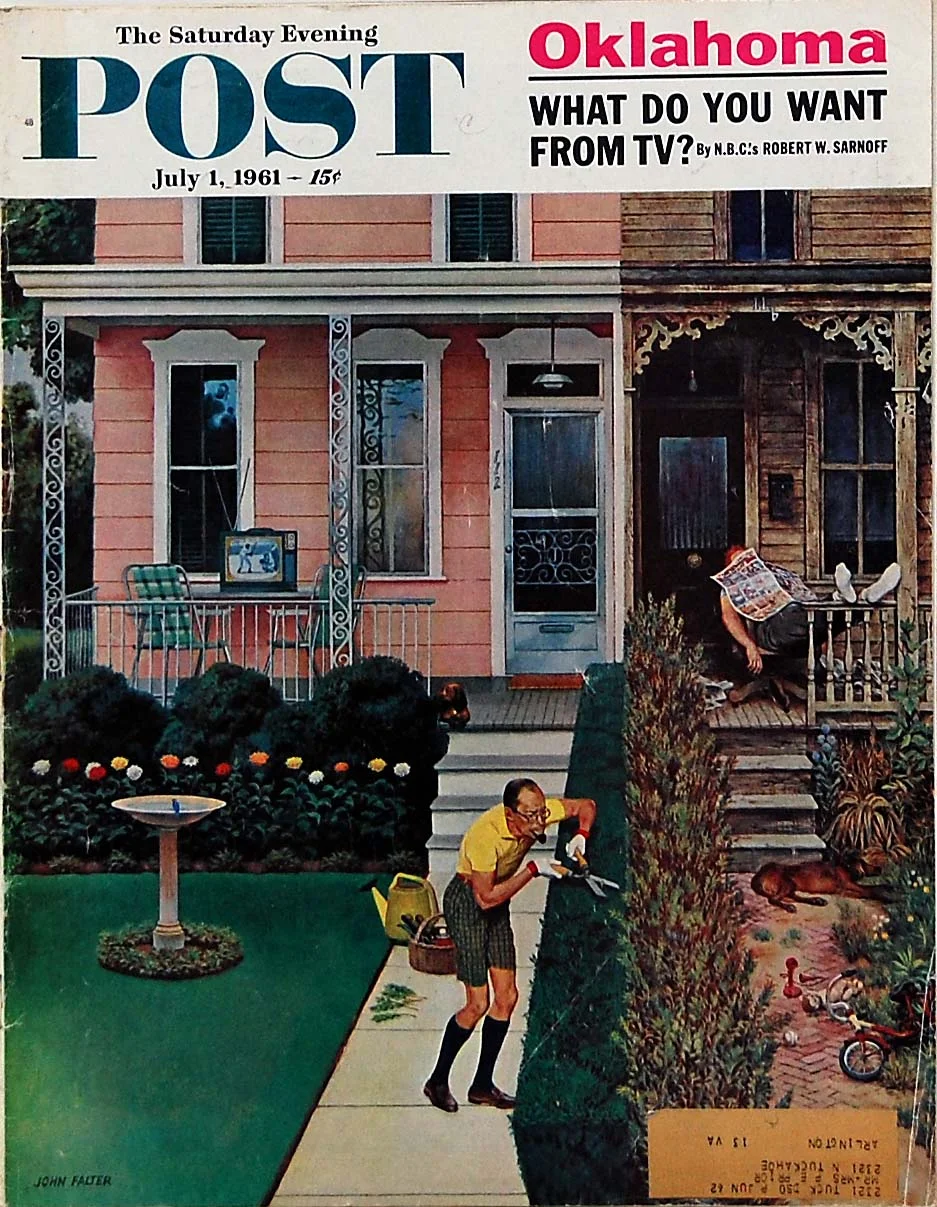

John Falter's cover shows us that twin homes, like twin humans, usually dress differently as they get on in years. At the residence on our right we find a reclining retriever at the foot of the steps and an irretrievable recliner at the top of the steps, in an office chair. We deduce that both Red and his neighbor, Mr. Jones, seek relaxation in activities which provide a change of pace from their workaday pursuits. Red is a handyman who likes to assume the posture of an executive, and Mr. Jones is an executive who enjoys playing handyman. Red has no desire to keep up with the Joneses, for he has observed a danger of over grooming; Red's head of hair is a jungle, but it flourishes; whereas Mr. Jones's hair seems to have been combed and plastered to within a couple of inches of its life.

September 23, 1961

ADOPTED BY: CARSON SELLS

Spanish architecture in Missouri? If such a state of affairs seems peculiar, consider that the unpredictable Show Me state even has a town named Peculiar (pop. 458), some twenty miles south of here, on U.S. 71. Our cover scene is in Kansas City, "the gateway to the Southwest," and you are looking at the intersection where U.S. 50, gateway to the Country Club Plaza shopping center, crosses J.C. Nichols Parkway. This elegant community of shops was conceived and built by Jesse Clyde Nichols (1880-1950), to whom the fountain in the foreground is a memorial. The scene appealed to artist John Falter because the Old World architecture seemed to symbolize our nation's roots--which is not to deny the notion expressed by lyricist Oscar Hammerstein in Oklahoma! that "everything's up-to-date in Kansas City."

October 7, 1961

ADOPTED BY: BOB & JO NEMAN

Nineteen moist commuters. See how they run. Scarcely a word of complaint about how the rain in suburbia seems to fall mainly when they detrain. Artist John Falter can afford to laugh at these rush-hour scurriers. Falter's studio is in his home and he painted the railroad station at nearby Gwynedd Valley, Pa., in his own good time, when the sun was shining.

October 28, 1961

ADOPTED BY: BILL & SUSAN SIPPLE

Monument Circle takes its name from the limestone memorial to soldiers and sailors at its center. And the circle is at the very center of Indianapolis, which is right in the middle of the Hoosier state. Artist John Falter discerned a faintly French flavor in this scene--perhaps because Indianapolis was planned on the pattern of Washington, D.C., which was laid out by a Frenchman. But consider the English Gothic architecture of Christ Church Cathedral at the left, the vaguely Tudor air of the neighboring Columbia Club, and the bluntly modern design of the Fidelity Building. French, English, or just plan American, the circle suits a city with a half-Greek name--a name so long that Indiana's capital is sometimes known as "Naptown."

December 2, 1961

ADOPTED BY: MARTIN & LESLIE FATTIG

The fox impudently seated on that turnpike medial strip is relishing one of the greatest triumphs of his life, for surely he has rarely been able to enjoy his laugh in full view of his victims. Artist John Falter know of at least three foxes living around his Pennsylvania home near which he painted this scene. (The background is real, the situation imaginary.) But whether or not the riders find another fox to chase, word of the turnpike dodge will spread quickly among the local Reynards. So the master of foxhounds might just as well go home, scarlet of coat and face, and search his map for better hunting grounds, fox-filled but turnpike-free.

February 3, 1962

ADOPTED BY: THE ROTARY CLUB OF FALLS CITY

The kids plugging up the hill can look forward to a swell ride down, but they've got a long pull ahead of them first. If only they knew it, there's an easier way to go up, especially if a patient but absentminded father is at hand. Rather obtusely we asked artist John Falter if he had painted all those vertical sled tracks lying on his side, propped on his left elbow Roman-banquet style. He had not, he replied pityingly but kindly--obviously he needed only to turn the canvas on it's side. Which is as good an explanation as any for the fact that his signature is headed up the hill too.

March 17, 1962

ADOPTED BY: DONNA CAMPBELL & LEE FRANTZ

New Castle, Del., (pop. 4469), on the busy Delaware River, is six miles south of the state's largest city, Wilmington, and two miles off the main highway. Once it was Delaware's capital. Founded in 1651, it was William Penn's landing place when he came to American in 1682. Penn is thought to have spent a night in the house at the extreme right of our cover. The spire atop the Court house (left foreground) was used as the center of a twelve-mile radius in part of the 1763-67 survey--to settle a boundary dispute-- that resulted in the Mason-Dixon Line, which later played a key part in United States history.

September 15, 1962

ADOPTED BY: SCOTT & SANDRA HARDENDORFF VOLKER

IN MEMORY OF PAUL HARDENDORFF

Part of the fun of owning a sports car stems from coping with minor inconveniences such as having to put up your top in a sudden rainstorm. Artist John Falter approached this "fun" with feeling. Once he owned a sports car himself--a 1947 English Singer Drop-Head Coupe with Self-Canceling Trafficators. It wasn't waterproof.

ADOPTED BY: NORM & SHARON HONEA HORN

In the early 1960's, Post switched to photography for it's covers, but John was asked to do one more for the Winter of 1971 issue. He used his daughter Suzanne and their country Pennsylvania home for models. John's interest then turned to historical paintings. He completed over 200 in the field of Western art with emphasis on the migration of 1843-1880 from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains. He was honored by his peers with election to the Illustrators Hall of Fame in 1976, and with membership in the National Academy of Western Art in June of 1978.

All covers are copyright of the Saturday Evening Post Society.